A Day in the Life

No day goes as planned is my personal mantra out here and yesterday was no exception.

We had two objectives: to travel to the MUA Mission about one or two hours from here to see Father Brenden O’Shay who had housed medical students for us last year and revisit the hospital that has served as our training site. The other goal was to do this in the daylight. Traveling at night along narrow roads full of villagers either walking or riding bicycles can be nerve racking at best and downright dangerous on occasions.

It was Sunday and we had heavy rains during the night. We had made a commitment to attend the CCAP (Central Church of Africa-Presbyterian) which was scheduled for 9:30, the time we arrived. But the rains delayed the service for over an hour.

I rushed over the tarmac main road and along the 1 ½ miles of dirt path/road to our cottage, leaving Ruth and two students at the church to deliver some small gifts to a family who lived nearby. We were multitasking. This is always a mistake out here.

Returning to the road, I was stopped by three uniformed police. I was not allowed to enter the road. The President and his entourage would be passing by in a few minutes and the road must be cleared of traffic. A few minutes became 15 then 30, then 60 plus. Cars, trucks, businessmen, fisherman all were pulled off to the little side road. None were pleased. I did the doctor trick. I was scheduled to see a patient at the MUA hospital. Papani bwana (sorry sir). What if the patient dies? Papani bwana! Finally after one and a half hours, a convoy of 25 cars and a bus lights on and traveling at high speed passed by. We were later to learn he was on a crop inspection not stopping just observing as the convoy buzzed down the road.

At last we were on our way. We had rehabilitated our car. This is needed annually and we are used to it. The previously reported thirst problems for both oil and water (every one hour of travel) had been fixed. The engine had new pistons and rings before we arrived. We replaced the radiator and bought new tires. Since we arrived, it had been purring along.

One and a half hours towards the MUA mission in the middle of nowhere, traveling at 80 kilometers an hour, the engine just quit, as if someone had turned off the key. Wow! No roadside service here, not even our AARP towing assistance. By now it was 3:00 pm and would be pretty much pitch black by 6pm.

I looked at the engine. It had water and oil. The battery looked fine and I could find no loose wires. I let it cool down. Not only did it not start, but sounded different when the engine turned over. Recheck the engine! Ah! A loose cover at the end of the engine block easily removed and voila - the timing belt had broken. This car was not going to be repaired by the roadside.

Out here you call your friends. You depend upon them. Plus the great innovation in this part of the world, we discovered when first returning for these annual trips 10 years ago were functioning cell phones.

I called Mr. Sibale, the director of MCV. “Bwana, the car is buggered and we are stuck”. His response, “ I will get the mechanic and I am on my way”, no hesitation, no delay.

And now what do you do for two hours. By this time we have two college graduates, Ricardo from Chicago and Samantha from Anchorage both volunteer teachers, plus Peter our Malawian IT person for the Malawi Children’s Village. All are nonplussed by this and proceed to have Ricardo teach them the salsa using music from his ipod in the middle of the tarmac road which has not seen a car pass by for at least an hour.

Almost two hours later we see Sibale”s car in a distance and as it approaches, a tow bar is suspended and hanging out the front driver and rear passenger window. A “ site for sore eyes”. As we heaped on thanks for the rescue, he and his wife Faith could not count the number of times they have done this or been towed themselves. It turns out that every family with a car has a steel tow bar as standard auxiliary equipment. In fact we were close by. He had traveled for hours in the past to tow folks back to town.

So late in the afternoon, steel tow bar attached, flashing warning lights a blazing, and me at the steering wheel and watching for a slack tow bar, we limp back to home. It was uneventful except after dark and staring at the tow bar for well over an hour being illuminated by his flashing tail lights, I was glad I did not have any seizure tendency.

Home at last after dark about 7:30 pm. I told Ruth we were lucky. I had though this would have been an all night affair. But unknown to us, more was still to come.

I have mentioned in a previous note the worry about rain around here. We had rain the night before, not enough but a good start. At about 2 am Monday morning in what must have been an answer to the ablations of the villagers, the rain gods awoke, and the water that fell equaled that going over Victoria Falls on the great Zambezi River. Now thatched roofs are good, but they have their limitations. What is that dripping in my face? Up with a flashlight for now of course the power is out and there is water fairly straight down the house-lots of it. This included one of our beds that we had used to sort out papers and pictures. There was water on the portable printer (it still works). With the rain still coming, the only answer is to move from the dripping spots. Put towels over what was not moveable and wait until morning.

It was Biblical. We know that the first part of Genesis says the earth was created in seven days. I never believed it, nor did I believe that whole lakes could be created overnight, but it happened.

In the morning light, there were lakes everywhere and what used to be dry creek beds were raging rivers eroding their banks at every turn and creating new channels. Everyone with a thatched roof was wet. The villagers had the toughest time. Many of their walls are just mud dried bricks that work well if they are kept dry. Not this time, they melt away. When you talk to them they don’t talk about their nyumba (village hut), they say their maize gardens have enough water. Out here it is a mater of priorities. Houses can be repaired. A lost growing season, and there is famine the following year.

And so, one 24 hour period- a day in the life.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Monday, March 15, 2010

“I wave my hand to all I see”

Have your heard or do you remember the old camp song with the above line. And the next line is “and they wave back to me”. I think of this often in this little corner of the world, whether we are driving the car or running on the village dirt road at 5:10 am. (You run just at daybreak here to miss the morning sun). We are surrounded by villagers who live in view just outside our thatched roof, baked brick, running lake water house. They really know how to smile and meet you with warm Chichewa or Chiyao greetings. We are known around here, but even strangers are given the same reception. Travelers from the counties that surround Malawi comment on this country’s hospitality.

This has led their president to remark, “we are a rich people, just poor in resources”. And poor they are …even the professionals. Clinical officers ( three of four years of training after secondary school), the backbone of the health care system in the country, earn about $180/month; teachers - $150/month; House keepers and hotel workers - $40/month. Living is expensive by their standards. A family of six, two adults and four children, eat a 50 kilo bag of chimanga (maize), their staple, per month. A fifty kilo bag costs $20.

Everyone, including the professional class must have a garden for food to supplement their income. If there are two working parents, they either work in their gardens before their day jobs or hire someone to work their garden for them. And there are no mechanized farming machines. The thousands and thousands of hectares that one sees planted with maize this time of year, is done with a large bladed hoe called a Mkhasu . The maize will be left to dry on the stalk and then harvested and stored by their village home and it must last the rest of the year. A bad rainy season (December, January, and February) and there is famine by this time next year. There are no safety nets. Just now everyone is worried. They had promising early rains, the maize is tasseled, but they have not had any significant rain for the last week. A poor crop now and they will have a repeat performance of the famine of 2002 and 2005.

We find among the Malawians folks who are just as clever, intelligent, and industrious as anyplace in our country. So why are they so poor and we are so rich? They were born in Malawi and we were born in the United States. It is an accident of birth.

Their kindness to us is almost beyond description. We attend a little village Anglican Church, the one that sponsors the HIV/AIDS support group that I mentioned before. Last Sunday night, long after dark, two of the church leaders on one motorcycle stopped by our cottage and said the elders of the congregation have decided to have a church supper in our honor tomorrow night. Yesterday, Catherine , one of the community field workers (the bed net lady), invited us to lunch at her somewhat upgraded village house for a traditional meal of nsima (a thick maize porridge) and ndiwo ( relish dish into which the nsima is dipped). All is eaten by hand after you are presented with a pitcher of water and basin to wash you hands (and the nsima is less likely to stick if your hands are

wet- a little trick we have learned over the years). For our village neighbors just around our cottage in return for a clinic visit on our porch, we receive two ears of maize or maybe an egg or two.

Malawians are very generous, and they are quite open.

After you are here for a while, and especially if you are a repeat visitor, you begin to hear the “secrets of the village”. This is about this time that Ruth and I say it is time to return home. The secrets used to be the whispered rumors of who was suspected to be HIV positive. Fortunately now this is becoming more public knowledge, treatment is available, and the community is coming to understand that this is no longer a death sentence.

Now the whispers are problems with family members, long standing disputes between whom we had assumed were friends, husbands who have cheated on their wives (sounds like just where we came from). It is information we just don’t need to know, but it reminds us of the universal nature of human relationships.

As I write this note at our almost open air dining room table, seeing a few goats and villagers on their way home and Cape Turtle doves singing in the distance, I am reminded how very much we feel at home here and how this largely forgotten country has influenced our lives.

We started our marriage here, learning how to negotiate our relationship that has served us well over the years. It changed our careers. Most of you know that neither of us had considered health care until our Peace Corps experience here in the 60’s.

Now, our annual trips for us refresh life’s priorities. In all the “noise” of our everyday lives, we tend to forget what is truly important: good health; loving relationships; adequate food, water, clothes and a dry roof; opportunities for an education and a spiritual life. Adequate but not excessive is all that is needed. This is a lesson we relearn each year.

This has led their president to remark, “we are a rich people, just poor in resources”. And poor they are …even the professionals. Clinical officers ( three of four years of training after secondary school), the backbone of the health care system in the country, earn about $180/month; teachers - $150/month; House keepers and hotel workers - $40/month. Living is expensive by their standards. A family of six, two adults and four children, eat a 50 kilo bag of chimanga (maize), their staple, per month. A fifty kilo bag costs $20.

Everyone, including the professional class must have a garden for food to supplement their income. If there are two working parents, they either work in their gardens before their day jobs or hire someone to work their garden for them. And there are no mechanized farming machines. The thousands and thousands of hectares that one sees planted with maize this time of year, is done with a large bladed hoe called a Mkhasu . The maize will be left to dry on the stalk and then harvested and stored by their village home and it must last the rest of the year. A bad rainy season (December, January, and February) and there is famine by this time next year. There are no safety nets. Just now everyone is worried. They had promising early rains, the maize is tasseled, but they have not had any significant rain for the last week. A poor crop now and they will have a repeat performance of the famine of 2002 and 2005.

We find among the Malawians folks who are just as clever, intelligent, and industrious as anyplace in our country. So why are they so poor and we are so rich? They were born in Malawi and we were born in the United States. It is an accident of birth.

Their kindness to us is almost beyond description. We attend a little village Anglican Church, the one that sponsors the HIV/AIDS support group that I mentioned before. Last Sunday night, long after dark, two of the church leaders on one motorcycle stopped by our cottage and said the elders of the congregation have decided to have a church supper in our honor tomorrow night. Yesterday, Catherine , one of the community field workers (the bed net lady), invited us to lunch at her somewhat upgraded village house for a traditional meal of nsima (a thick maize porridge) and ndiwo ( relish dish into which the nsima is dipped). All is eaten by hand after you are presented with a pitcher of water and basin to wash you hands (and the nsima is less likely to stick if your hands are

wet- a little trick we have learned over the years). For our village neighbors just around our cottage in return for a clinic visit on our porch, we receive two ears of maize or maybe an egg or two.

Malawians are very generous, and they are quite open.

After you are here for a while, and especially if you are a repeat visitor, you begin to hear the “secrets of the village”. This is about this time that Ruth and I say it is time to return home. The secrets used to be the whispered rumors of who was suspected to be HIV positive. Fortunately now this is becoming more public knowledge, treatment is available, and the community is coming to understand that this is no longer a death sentence.

Now the whispers are problems with family members, long standing disputes between whom we had assumed were friends, husbands who have cheated on their wives (sounds like just where we came from). It is information we just don’t need to know, but it reminds us of the universal nature of human relationships.

As I write this note at our almost open air dining room table, seeing a few goats and villagers on their way home and Cape Turtle doves singing in the distance, I am reminded how very much we feel at home here and how this largely forgotten country has influenced our lives.

We started our marriage here, learning how to negotiate our relationship that has served us well over the years. It changed our careers. Most of you know that neither of us had considered health care until our Peace Corps experience here in the 60’s.

Now, our annual trips for us refresh life’s priorities. In all the “noise” of our everyday lives, we tend to forget what is truly important: good health; loving relationships; adequate food, water, clothes and a dry roof; opportunities for an education and a spiritual life. Adequate but not excessive is all that is needed. This is a lesson we relearn each year.

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Growth Charts take on new meaning

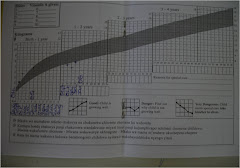

How well a child grows says a lot about the family and community in which they live. All of our kids have them and it is a rare day that you find an unusual one. They are a simple graph. The column on the left side of the page is weight and the row at the bottom is the child’s age in months until age five. On a 6 month interval or more frequent intervals you put a dot that corresponds to the child’s weight and age that day. Over time, normally you see a steady and predictable weight gain as the child gets older. They are usually so normal that one might ask are they of any value.

Come to Malawi. Growth charts are like tree rings which document good and bad growing years, fires in the forest, damage from insects. When we are asked to examine large numbers of children, we ask to see their growth charts. It is easy to sort the sick from the well. The abnormal growth charts are dramatic. They record the hunger times (njala), death of the mother, and a chronic illness like malaria, worms, or asthma. Even functional defects of one’s heart valves can affect a child’s growth.

Look at the one on the right. This one is from Malawi and the gray shaded area is where 95% of the children should fall as they grow. This child was above normal for weight and age when he was born (above the gray area) but by two months of age something happened and by the time he was seen again when he was 14 months, he had fallen below the normal growth curve. This is a child you would want to see to find out what happened. The rest of the story is his mother died from complications of HIV/AIDS at 2 months. He was farmed out to relatives and not seen in any clinic until 14 months of age, and then while under supervision, began to grow again. This is a typical story. Being an orphan any where in the world is devastating. In Malawi it is life threatening.

Most of the orphan children in the Malawi Children’s Village catchment area have growth charts because they attend the under 5 clinics sponsored by the government. Unfortunately not all village children do.

For the last two days Ruth and I were able to accompany the MCV field workers, Catherine and Florence, to the villages to check on the orphans in their villages. We were accompanied by the MCV village volunteer for that village.

You come face to face with reality in the village. The 2 pm African sun slows your walking to a snail’s pace, you carry water, and plan on being in sweaty clothes for the rest of the day. No different for our African colleagues. From village hut to village hut you walk, announce your presence outside the usually well swiped dirt yard, and are invited in as they produce a grass mate for everyone to sit on.

And then the stories begin. This time of year most everyone is hungry. They have planted their new maize crop in December that will not be harvested until late March. There stored maize from last year’s crop is finished. This is the annual hunger time (Njala) sometimes better, sometime worse depending on the previous year’s rains. Last years rains were described as okay which translates to the “hungry time; but they will make it”. What do they eat? What ever they can scrounge from the land. The ubiquitous mango trees produce in December and early January, which helps cover this time period, but just now food of any kind is scarce. Yesterday we saw them collecting wild grass that had gone to seed. The seed is separated from the stalk, dried in the sun, pounded in a large (one foot wide) mortar; the hulls are winnowed from the minuscule kernel which is made into their staple thick porridge called nsima. I have no idea of the nutritional value, but this takes an enormous amount of work for the small calories it produces.

Obesity is virtually non existent outside the two main cities.

After hunger the issue is usually Malaria….I am not always sure of the diagnosis. Everyone who has a headache or a fever says they have malaria; however the medical literature suggests only 30% do. I do know that Ruth has cured a number of cases of village diagnosed “malaria” by handing out a few tablets of Advil.

It is a dangerous disease, worse if you are under 5 or HIV positive. The under five mortality for Malawi is in the 15% to 20% range. Half of the deaths are due to malaria. If you are HIV positive, have not been religious about taking you HIV medicines, the malaria parasite can get to your brain. Cerebral malaria can be a death sentence and frequently is.

For the kids under five, sleeping under a bed net ($4.00) will reduce the malaria rate by 60 -70 percent. For the HIV positive patient, taking your HIV medications and early treatment of malaria are the answer.

But now back to the growth charts. This morning Ruth and I were asked to examine 52 children in a nearby village school. They were our equivalent of first, second and third graders. Fifty two is an impossible number-some with growth charts and some not, but we did have a record of their weights since they had been at school. By using a combination of growth charts and asking the head Malawian teacher who she was worried about, we had a manageable number of kids to see. Here is a disease menu from today: multiple cases on anemia diagnosed when you see gray instead of a pink conjunctiva surface, (the usual cause, previous malaria or worms, I cannot tell which), two enlarged and very firm spleens from recurring malaria, two cases of undiagnosed epilepsy frequently thought out here to come from witchcraft, multiple cases of a fungal infection of the scalp which is very common, and various types of infected skin lesions, including hookworms that invade the web between your toes softened by the wet grass and mud of the rainy season. The worms set up shop just under the skin of the foot just behind the toes. It was a very productive morning.

Often what started out as a simple medical problem easily treated is first seen after such a long delay, that we have a difficult time putting the clinical picture together. Many are exacerbated by lack of soap, clean water, enough food, and simple bed nets.

Malawi must be at the top of the list for the most gracious and friendly country that one could find. The do not deserve the life that most of them must live in 2010.

Come to Malawi. Growth charts are like tree rings which document good and bad growing years, fires in the forest, damage from insects. When we are asked to examine large numbers of children, we ask to see their growth charts. It is easy to sort the sick from the well. The abnormal growth charts are dramatic. They record the hunger times (njala), death of the mother, and a chronic illness like malaria, worms, or asthma. Even functional defects of one’s heart valves can affect a child’s growth.

Look at the one on the right. This one is from Malawi and the gray shaded area is where 95% of the children should fall as they grow. This child was above normal for weight and age when he was born (above the gray area) but by two months of age something happened and by the time he was seen again when he was 14 months, he had fallen below the normal growth curve. This is a child you would want to see to find out what happened. The rest of the story is his mother died from complications of HIV/AIDS at 2 months. He was farmed out to relatives and not seen in any clinic until 14 months of age, and then while under supervision, began to grow again. This is a typical story. Being an orphan any where in the world is devastating. In Malawi it is life threatening.

Most of the orphan children in the Malawi Children’s Village catchment area have growth charts because they attend the under 5 clinics sponsored by the government. Unfortunately not all village children do.

For the last two days Ruth and I were able to accompany the MCV field workers, Catherine and Florence, to the villages to check on the orphans in their villages. We were accompanied by the MCV village volunteer for that village.

You come face to face with reality in the village. The 2 pm African sun slows your walking to a snail’s pace, you carry water, and plan on being in sweaty clothes for the rest of the day. No different for our African colleagues. From village hut to village hut you walk, announce your presence outside the usually well swiped dirt yard, and are invited in as they produce a grass mate for everyone to sit on.

And then the stories begin. This time of year most everyone is hungry. They have planted their new maize crop in December that will not be harvested until late March. There stored maize from last year’s crop is finished. This is the annual hunger time (Njala) sometimes better, sometime worse depending on the previous year’s rains. Last years rains were described as okay which translates to the “hungry time; but they will make it”. What do they eat? What ever they can scrounge from the land. The ubiquitous mango trees produce in December and early January, which helps cover this time period, but just now food of any kind is scarce. Yesterday we saw them collecting wild grass that had gone to seed. The seed is separated from the stalk, dried in the sun, pounded in a large (one foot wide) mortar; the hulls are winnowed from the minuscule kernel which is made into their staple thick porridge called nsima. I have no idea of the nutritional value, but this takes an enormous amount of work for the small calories it produces.

Obesity is virtually non existent outside the two main cities.

After hunger the issue is usually Malaria….I am not always sure of the diagnosis. Everyone who has a headache or a fever says they have malaria; however the medical literature suggests only 30% do. I do know that Ruth has cured a number of cases of village diagnosed “malaria” by handing out a few tablets of Advil.

It is a dangerous disease, worse if you are under 5 or HIV positive. The under five mortality for Malawi is in the 15% to 20% range. Half of the deaths are due to malaria. If you are HIV positive, have not been religious about taking you HIV medicines, the malaria parasite can get to your brain. Cerebral malaria can be a death sentence and frequently is.

For the kids under five, sleeping under a bed net ($4.00) will reduce the malaria rate by 60 -70 percent. For the HIV positive patient, taking your HIV medications and early treatment of malaria are the answer.

But now back to the growth charts. This morning Ruth and I were asked to examine 52 children in a nearby village school. They were our equivalent of first, second and third graders. Fifty two is an impossible number-some with growth charts and some not, but we did have a record of their weights since they had been at school. By using a combination of growth charts and asking the head Malawian teacher who she was worried about, we had a manageable number of kids to see. Here is a disease menu from today: multiple cases on anemia diagnosed when you see gray instead of a pink conjunctiva surface, (the usual cause, previous malaria or worms, I cannot tell which), two enlarged and very firm spleens from recurring malaria, two cases of undiagnosed epilepsy frequently thought out here to come from witchcraft, multiple cases of a fungal infection of the scalp which is very common, and various types of infected skin lesions, including hookworms that invade the web between your toes softened by the wet grass and mud of the rainy season. The worms set up shop just under the skin of the foot just behind the toes. It was a very productive morning.

Often what started out as a simple medical problem easily treated is first seen after such a long delay, that we have a difficult time putting the clinical picture together. Many are exacerbated by lack of soap, clean water, enough food, and simple bed nets.

Malawi must be at the top of the list for the most gracious and friendly country that one could find. The do not deserve the life that most of them must live in 2010.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

Going Offline in Malawi

A trip to Malawi requires an attitude adjustment, a different way of thinking. It happens when we start packing. You pack toilet paper, start saving sheets of paper only used on one side and Ruth says “save those zip lock plastic bags-they are a premium now”

Malawi is known as the “Warm Heart of Africa” for the friendliness of the people. It is also in the “have not” part of the planet, 5th from the bottom in world poverty. Out and away from the two major cities, it is pure subsistence. You grow it, raise it or catch it, or you don’t eat. Your house is made of materials from the land next door: mud dried bricks, bamboo roofing poles and grass on the roof

We try to pack accordingly: one suitcase for the both of us for a one month visit. We bring several “luxury item” beyond toilet paper, bath soap, small laptop, a good pair of binoculars, and a few medical supplies. And you know what, we have more than we need and we live very well. It forces one of life’s major questions, “how much is enough”? The answer: a heck of a lot less of what we have in Anchorage, and a lot more than what the villagers have in Malawi.

With several of our Malawian colleagues and friends, we met with 37 HIV positive folks yesterday (Sunday) in a support group in a nearby village. All were on adequate HIV medicines. We asked what they were most worried about. The answer was immediate. ….enough food to eat and for the women also a dry roof to sleep under because most of their husbands had died from the complications of HIVAIDS.

For Ruth and I our trip to Malawi is like hitting the reset button. The more fundamental issues in life pop back into focus. For a month we are in the offline mode both literally and figuratively.

First you take an electronic holiday –cell phones don’t ring; the internet does not work; or is so sloooow that you wish it didn’t work, forget about TV and the two small national papers are devoid of news from the United States. At home I am a news junkie. But after about three days of withdrawal, you realize you are more relaxed, the pace is slowed and you are hearing more birds singing the early morning.

And then there is the interesting part about entering a different world reality that puts your Alaska life offline. It is hard to explain. The immediacy of the daily mini crises at home with work, in the family and with friends are set aside and fade from memory. They are replaced here with others and usually more basic issues among our friends, neighbors and folks who approach us during our daily activities: enough food to eat, clean water to drink, a thatched roof that does not leak, clothes to wear. It is a great mind adjuster.

It is just a different reality. Some of the life’s major issues are the same: Death of loved ones, serious illness, wayward teenagers and always a concern about no money. Even in a subsistence culture some money is needed: tea, sugar, school fees for kids going to secondary school, money for transport for going to the hospital. And the social ills of any society are all pretty much the same: jealously of what your neighbor has, rumor mongering, infidelity, alcoholism. The longer that Ruth and I are here, the more sameness we see; not the differences.

You don’t romanticize. For Malawians life is tough. There is no social safety net. You and your village are on your own. To the extent that institutional support is available, it comes from the churches and mosques (also very poor), and the various NGO’s (non governmental organizations = non profits) scattered throughout the country.

So how can you and we help? Here is what we have been learning over the years. Most of our ideas of what should be done, don’t work. It takes local knowledge, leadership and commitment to make a difference.

Here is how you have to adjust your thinking: The country was out of petrol. Even the police and the military did not have any. Zambian petrol trucks were supplying all the petrol to landlocked Malawi and Zambia ran out of truck tires. Ah, the locals say “this is Malawi” and get on with their work as best they can. Donated equipment from good-hearted foreigners, everything from office copiers, vehicles, laboratory equipment, water pumps, desperately needed and do make a contribution until they break. There are no replacement parts, and for the more sophisticated items, no one to fix them even if the parts were available. The mantra that you hear about simple and appropriate technology for this part of the world is spot on.

And Malawians are very resourceful. Equipment simply designed using easily available materials are ideal. Malawians will make sure they work and keep them running. Take for example the Mangochi (where we live) equivalent of “duck tape”. In the market and at multiple places along the roadway, we were seeing what looked like smoked strips of meat, except they were longer and blacker (inch wide and three to four feet long). It is the inside cord striped from used car tires. Tie links together and it is used for rope; peel off individual several strands, and it ties together the bamboo uses make your roof; peel off just one strand and use it to hang jewelry around your neck. The rest of the tire , cut , shaped and used for the soles of your shoes. They have made recycling into a science.

So again the question is how can you help? The guiding principle has to be “local solutions for local problems”. As an outsider the problems are easy to identify and too often in the past, we all thought we had the workable solution. Not true. The local folks have to puzzle it out, and we have to listen. They know what will work and not work.

A second and just as important thought is most of the significant problems out here do not exist in isolation. One cannot tackle just one social issue. They don’t exist in isolation. To tackle one, you must work on the others also. It is a jigsaw puzzle. All the pieces must be found and fit, before the picture is complete.

The Malawi Children’s Village (MCV) is a good example. It is Malawian designed and owned. This mission is simple. Give the HIVAIDS orphans in the 36 villages that surround the little campus, the same or even better chance at life, as if they had their own parents. In reality it is a community development program focused on orphans.

For these kids, it is not just providing an opportunity to go to a good school. It also means enough food to eat, a dry roof to sleep under, clothes to wear, and a place to go if you get sick. Hopefully living with a guardian or grandparent who would provide the love and stability your parents would have. It takes a village to raise a child!

The response from MCV over the past 12 years has been comprehensive: village irrigation projects; the Anchorage school to school program to beef up the village primary schools; an in house vocational training and secondary school; supplying clothes and blankets and housing repairs; a bed net program for children under five establishing village based MCV volunteers who independently watch out for the welfare of the orphans in their village. These efforts have benefited the whole village. The village improves; the life of the orphans in the villages rises with the tide.

The results have been remarkable. Ten of the top students in this year’s senior class of 80 are orphans. Several of the orphans from earlier in the program are now teaching in the secondary school. The bed net program has dramatically reduced the rate of Malaria. Primary schools have desks, paper and pencils. Last years graduation class had the second highest pass rate on the national exams among the 10 secondary schools in this district.

You have made this happen! And your contributions go far. The USA Malawi Board is completely volunteer. There is no paid staff. Our reasons to come to Malawi include making sure the contributions that we send over are spent appropriately. This trip our focus is on sustainability.

Malawi and MCV are a wonderful, confusing, complicated, and satisfying place to volunteer. It does reset you priorities and we feel privileged to be able to work and participate in this part of the world.

Malawi is known as the “Warm Heart of Africa” for the friendliness of the people. It is also in the “have not” part of the planet, 5th from the bottom in world poverty. Out and away from the two major cities, it is pure subsistence. You grow it, raise it or catch it, or you don’t eat. Your house is made of materials from the land next door: mud dried bricks, bamboo roofing poles and grass on the roof

We try to pack accordingly: one suitcase for the both of us for a one month visit. We bring several “luxury item” beyond toilet paper, bath soap, small laptop, a good pair of binoculars, and a few medical supplies. And you know what, we have more than we need and we live very well. It forces one of life’s major questions, “how much is enough”? The answer: a heck of a lot less of what we have in Anchorage, and a lot more than what the villagers have in Malawi.

With several of our Malawian colleagues and friends, we met with 37 HIV positive folks yesterday (Sunday) in a support group in a nearby village. All were on adequate HIV medicines. We asked what they were most worried about. The answer was immediate. ….enough food to eat and for the women also a dry roof to sleep under because most of their husbands had died from the complications of HIVAIDS.

For Ruth and I our trip to Malawi is like hitting the reset button. The more fundamental issues in life pop back into focus. For a month we are in the offline mode both literally and figuratively.

First you take an electronic holiday –cell phones don’t ring; the internet does not work; or is so sloooow that you wish it didn’t work, forget about TV and the two small national papers are devoid of news from the United States. At home I am a news junkie. But after about three days of withdrawal, you realize you are more relaxed, the pace is slowed and you are hearing more birds singing the early morning.

And then there is the interesting part about entering a different world reality that puts your Alaska life offline. It is hard to explain. The immediacy of the daily mini crises at home with work, in the family and with friends are set aside and fade from memory. They are replaced here with others and usually more basic issues among our friends, neighbors and folks who approach us during our daily activities: enough food to eat, clean water to drink, a thatched roof that does not leak, clothes to wear. It is a great mind adjuster.

It is just a different reality. Some of the life’s major issues are the same: Death of loved ones, serious illness, wayward teenagers and always a concern about no money. Even in a subsistence culture some money is needed: tea, sugar, school fees for kids going to secondary school, money for transport for going to the hospital. And the social ills of any society are all pretty much the same: jealously of what your neighbor has, rumor mongering, infidelity, alcoholism. The longer that Ruth and I are here, the more sameness we see; not the differences.

You don’t romanticize. For Malawians life is tough. There is no social safety net. You and your village are on your own. To the extent that institutional support is available, it comes from the churches and mosques (also very poor), and the various NGO’s (non governmental organizations = non profits) scattered throughout the country.

So how can you and we help? Here is what we have been learning over the years. Most of our ideas of what should be done, don’t work. It takes local knowledge, leadership and commitment to make a difference.

Here is how you have to adjust your thinking: The country was out of petrol. Even the police and the military did not have any. Zambian petrol trucks were supplying all the petrol to landlocked Malawi and Zambia ran out of truck tires. Ah, the locals say “this is Malawi” and get on with their work as best they can. Donated equipment from good-hearted foreigners, everything from office copiers, vehicles, laboratory equipment, water pumps, desperately needed and do make a contribution until they break. There are no replacement parts, and for the more sophisticated items, no one to fix them even if the parts were available. The mantra that you hear about simple and appropriate technology for this part of the world is spot on.

And Malawians are very resourceful. Equipment simply designed using easily available materials are ideal. Malawians will make sure they work and keep them running. Take for example the Mangochi (where we live) equivalent of “duck tape”. In the market and at multiple places along the roadway, we were seeing what looked like smoked strips of meat, except they were longer and blacker (inch wide and three to four feet long). It is the inside cord striped from used car tires. Tie links together and it is used for rope; peel off individual several strands, and it ties together the bamboo uses make your roof; peel off just one strand and use it to hang jewelry around your neck. The rest of the tire , cut , shaped and used for the soles of your shoes. They have made recycling into a science.

So again the question is how can you help? The guiding principle has to be “local solutions for local problems”. As an outsider the problems are easy to identify and too often in the past, we all thought we had the workable solution. Not true. The local folks have to puzzle it out, and we have to listen. They know what will work and not work.

A second and just as important thought is most of the significant problems out here do not exist in isolation. One cannot tackle just one social issue. They don’t exist in isolation. To tackle one, you must work on the others also. It is a jigsaw puzzle. All the pieces must be found and fit, before the picture is complete.

The Malawi Children’s Village (MCV) is a good example. It is Malawian designed and owned. This mission is simple. Give the HIVAIDS orphans in the 36 villages that surround the little campus, the same or even better chance at life, as if they had their own parents. In reality it is a community development program focused on orphans.

For these kids, it is not just providing an opportunity to go to a good school. It also means enough food to eat, a dry roof to sleep under, clothes to wear, and a place to go if you get sick. Hopefully living with a guardian or grandparent who would provide the love and stability your parents would have. It takes a village to raise a child!

The response from MCV over the past 12 years has been comprehensive: village irrigation projects; the Anchorage school to school program to beef up the village primary schools; an in house vocational training and secondary school; supplying clothes and blankets and housing repairs; a bed net program for children under five establishing village based MCV volunteers who independently watch out for the welfare of the orphans in their village. These efforts have benefited the whole village. The village improves; the life of the orphans in the villages rises with the tide.

The results have been remarkable. Ten of the top students in this year’s senior class of 80 are orphans. Several of the orphans from earlier in the program are now teaching in the secondary school. The bed net program has dramatically reduced the rate of Malaria. Primary schools have desks, paper and pencils. Last years graduation class had the second highest pass rate on the national exams among the 10 secondary schools in this district.

You have made this happen! And your contributions go far. The USA Malawi Board is completely volunteer. There is no paid staff. Our reasons to come to Malawi include making sure the contributions that we send over are spent appropriately. This trip our focus is on sustainability.

Malawi and MCV are a wonderful, confusing, complicated, and satisfying place to volunteer. It does reset you priorities and we feel privileged to be able to work and participate in this part of the world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)